Last winter, the New England Aquarium’s Rescue and Rehabilitation made national news when more than 700 sea turtles came through our doors needing help. These cold-stunned turtles were found on the beaches of Cape Cod, brought to our rehabilitation facility in Quincy and were nursed back to health by our knowledgeable staff and volunteers.

This summer, visitors get to experience sea turtle rescue with our new interactive hospital. Have you ever wanted to see what it’s like to rehabilitate a turtle and be part of the life-saving crew? Now’s your chance to join turtle rescue team!

|

| This sign will greet you when you arrive. |

Upon entering the interactive hospital, you will receive a

quick overview of why sea turtles strand...but then it's straight to work!

Turtles are brought up from Cape Cod to the Aquarium's Quincy facility in

banana boxes, which are the perfect size for these small turtles, and nestled

in a towel for safe transport.

|

| Banana boxes full of replica turtles |

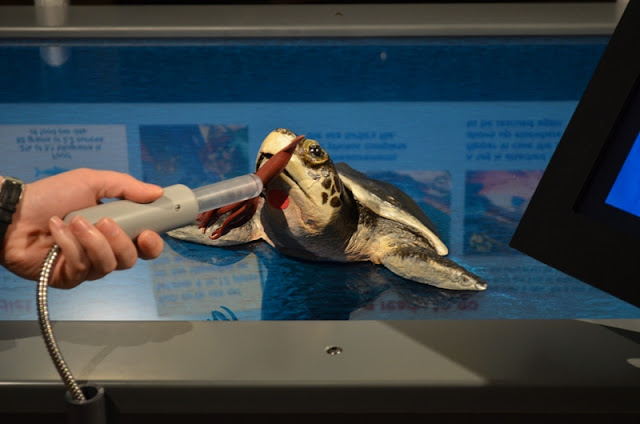

As their body temperature drops, a turtle's heartbeat may

slow to one beat per minute! Pick one of the three turtles and see if you can

find a heartbeat. Use the doppler to listen carefully…did you find it? Next,

listen to how the heartbeat of a cold-stunned turtle compares to a healthy

turtle. Quite a difference!

|

| Look and listen for a heartbeat |

Once a heartbeat has been established, it’s on to

diagnostics. First, a rescued turtle is stabilized with fluids and slowly

brought up to the right temperature. Then the hard work of identifying all of a

turtle's issues begins. Some turtles are just cold and dehydrated; some come in

with other issues. Scan the respiratory, digestive and skeletal systems of each

turtle to see what's wrong.

|

| Work to diagnose what's wrong |

|

| Scanning systems... |

Now that you have a diagnosis, learn what treatment

the turtle needs to get better and see the Aquarium staff in action as they

work to save animals and get them on the road to recovery.

|

| Working to solve the problem |

Now that the turtles

are on the mend, turn your attention to the next rehabilitation station. After

you’ve been sick, what do you want to do when you feel better? You want to eat,

of course! Turtles need to eat on their own before they can be released as they

will need to forage successfully to survive. At the feeding station, offer a

squid snack to the hungry turtles.

|

| Try your hand at feeding |

You may try to feed a turtle, and it won't

eat. Try again, however, and see how their appetites grow over time! One bite

closer to being released to their ocean home!

|

| Success! |

Thanks to the work that YOU did alongside our Aquarium team,

these turtles get a new lease on life. But this is just one piece of the turtle

rescue team puzzle. The job isn’t done. Throughout the Aquarium, you will see

what more we all can do to help sea turtles, as well as other species of turtles. Whether it is single-use

plastics or climate change, turtles face challenges in their environment, both across the world and in our own backyards.

Thankfully, the Turtle Rescue Team is growing, and together we can help solve

these challenges to ensure a successful future for turtles…and humans!

|

| Join the team! |